Abbeville Press just published a new edition of The Last Navigator, with a generous selection of the now-historic color photographs from my field trips to Satawal and updated text and diagrams. This is a lasting tribute to the spirit of The People of the Sea and their Elders, Chiefs, and Navigators. They took me in and taught me the Talk of Navigation so that it would be recorded for posterity and preserved in the face of modernization and Westernization.

I bought my first surfboard when I was 10 and my first sailboat when I was 13; I’ve been on or near the water ever since. After college I crewed on a yacht racing out to Hawaii, sailed the boat back to Seattle, and was undeniably hooked – I wanted to be at sea. The following year I became the first mate of a 103-foot schooner in the Mediterranean, and within months I was working for a boat builder in Antibes, in the South of France. After that, I delivered a 43-foot sloop from England to San Francisco via the Canaries, the Caribbean, Panama, the Galapagos, the Marquesas, and Hawaii. On that voyage I met my future wife.

After we married, I intended to return to my other, more profitable occupation: buying, renovating, and selling old houses. But that would have to wait.

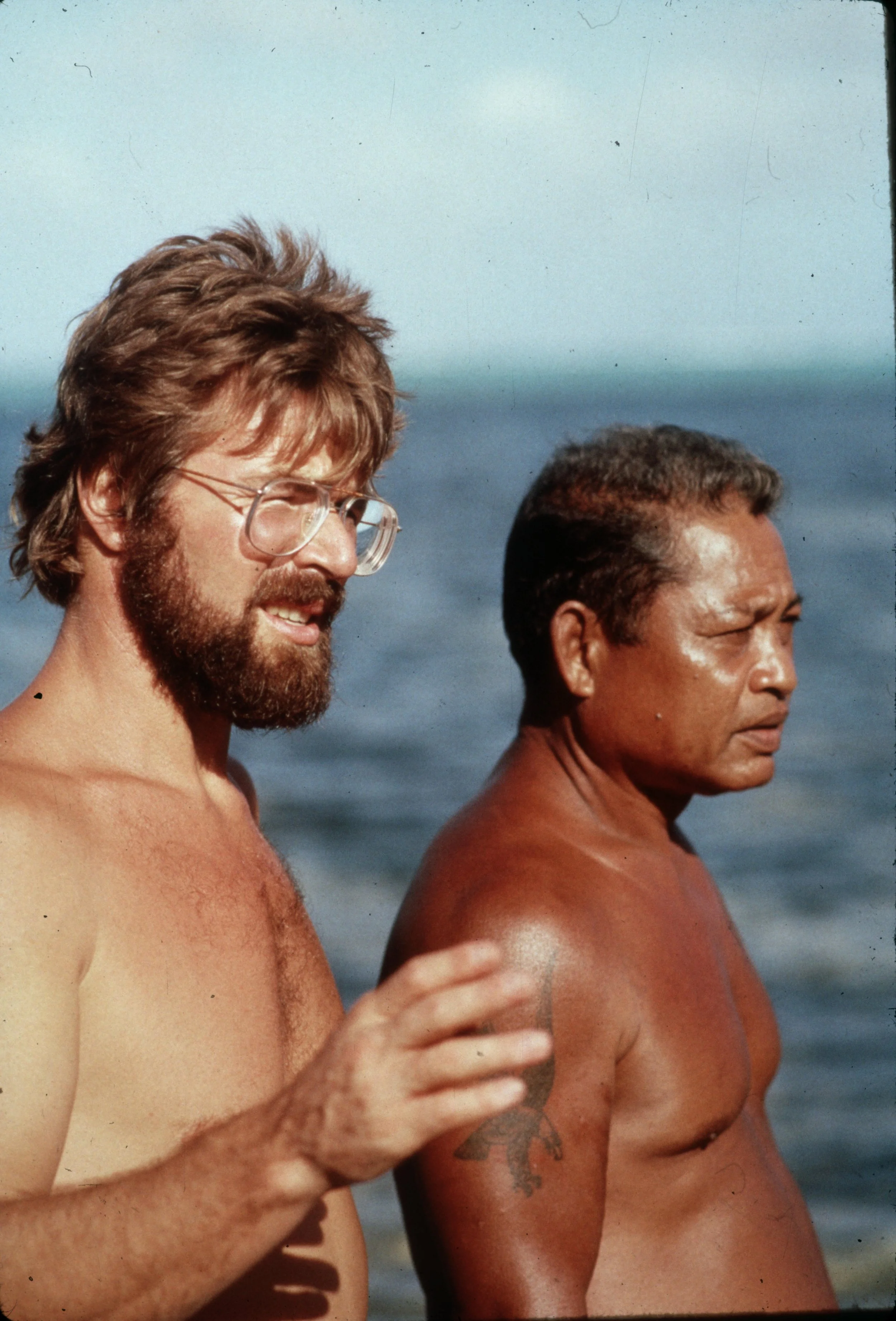

I had long imagined going to the Pacific islands to live among a seafaring people who were fully attuned to the sea’s natural rhythms. This quest led me to Micronesia, to Satawal Island, and to Mau Piailug, the youngest and one of the last of the fully initiated navigators, or paliuw.

In 1983, after a year of preliminary research, I journeyed to Satawal, hoping to apprentice with Piailug. He accepted me as his student and I stayed for six months. I returned in 1984 for another five months and then spent the next two years writing the manuscript. The Last Navigator was published in 1987. A 2025 updated and revised edition, including many more, now-historic, photographs is available at www.abbeville.com.

Shortly after the 1987 edition was published, serendipitously, in a trattoria in Venice, I met a British documentary film producer. We connected over bowls of squid ink pasta and a mutual love of adventure. By the end of the meal, we decided to produce a documentary based on The Last Navigator. We secured backing from Channel 4, Britain and WGBH, Boston and in 1987 and 1988 I returned to Micronesia. Using the 32-foot outrigger canoe Yaeninganoa, which I helped build, I sailed the six day passage with Piailug and his crew from Satawal to Saipan, the longest voyage his people have traditionally made. We had no radio, charts, compass, or other navigational equipment on board. André Singer, Martin Pick and their British film crew captured it all.

Going to Satawal and studying and voyaging with Piailug was the realization of a great, romantic dream. Much of opportunity is timing; five years earlier I would not have had the maturity to undertake the journey; five years later family responsibilities would have prevented me from doing so. It was a young man’s quest and I undertook it as a young man.

Then too, my arrival on Satawal coincided with a window in Piailug’s schedule. He had been fully involved in the Hokule’a project in Hawaii before I arrived and returned to Hawaii after I left. Had this timing been different, it may well have been impossible for me to study with Piailug at all.

There is also the matter of the age of the wise elders. By 1983, the old men realized that unless they bequeathed their knowledge to someone, it would die with their mortal frames. Indeed, our “father” Pwiitag died between my first and second field trips. Ewiyong was very old when I worked with him and knew he had not many years to live. Chief Otolik died on the field ship en route from the hospital on Yap back to Satawal. I was on that ship in late 1987, to arrange for the filming, and was able to bid him farewell as a son.

Micronesia’s is an oral tradition. As the old navigators have passed away, so has any opportunity to learn the Talk of the Sea, and the highly secret Talk of Light, both of which were taught to me with my promise that I would help to preserve it. I was indeed fortunate to go to Satawal when I did.

It has been forty years since I first met Piailug. As I look back, I am as impressed today as I was then by his generosity and his courage. He took me into his family, assumed responsibility for my material and political well-being, and taught me his navigation without reserve. The knowledge he gave me about navigation is considered priceless in his culture; the knowledge he gave me about myself, I have come to see, is priceless as well.

I often think of Piailug, and the fierceness and determination with which he defended a way of life he knew would die with the wise elders. He had the courage to live and teach and voyage fully aware he could never stem the tide of Westernization—Westernization that would change the character of his archipelago and might eliminate the very role of the paliuw as steward of his island’s heritage.